Data Scientist has commonly been referred to as the sexist job in the 21st Century over the last few years. Indeed, as a job which utilises state-of-the-art algorithms straight out of research papers, and often associated with futuristic inventions such as self-driving cars and human-like chatbots, what is not to like about being a data scientist!

But just as not every scientists are working on faster than light travel or time machines, not every data scientists are working on the frontier stuff that gets the most press and publicity. In fact, most data scientists are not working on self-driving cars or face recognition. For someone who wants to be a data scientist, this means the following – mastering deep learning, generative adversarial network or extreme gradient boosting may not actually increase your chance to become a data scientist, as only a very few jobs actually uses these tools. A better way to increase your chance in becoming a data scientist is to master tools or skill sets that are needed for most data scientist positions.

To understand what are the most desirable (hard) skills employers seek for in data science roles, we can look into data science job advertisements. After all, job posting directly reflect what employers are looking for in filling their data science roles. In particular, we could analyse recent online job posting to find out what skills appears the most in data scientist job ads. In Australia, the largest job posting sites are Seek, Indeed and Jora. Let’s focus on the postings on these three websites.

To analyse the job posting, we would need to scrap the information for each posting. This can be broken down into a two parts: extracting the links for each posting that comes up from a search of “data scientist” in each of the site, and extracting the actual text relating to the job posting from each extracted link. In both cases, the key comes down to decoding the html of the webpages of interest.

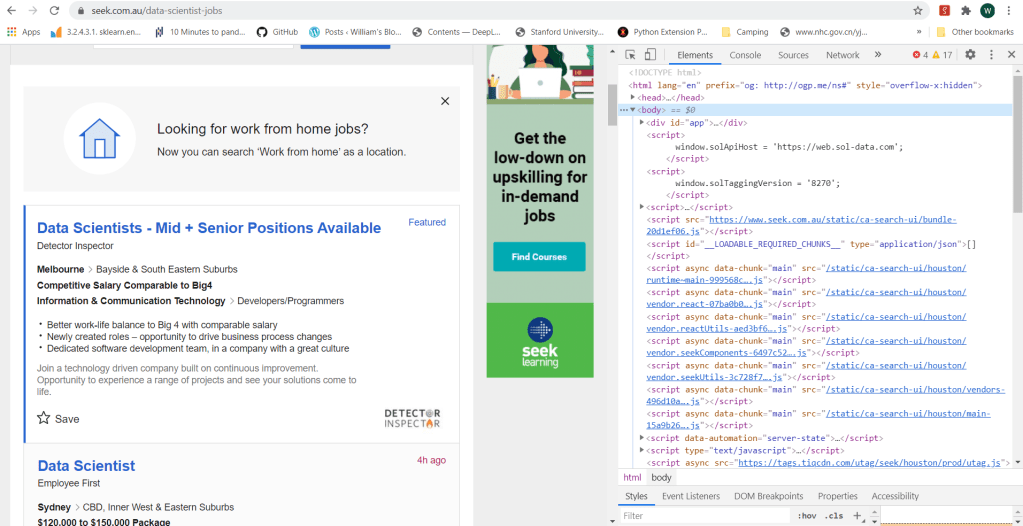

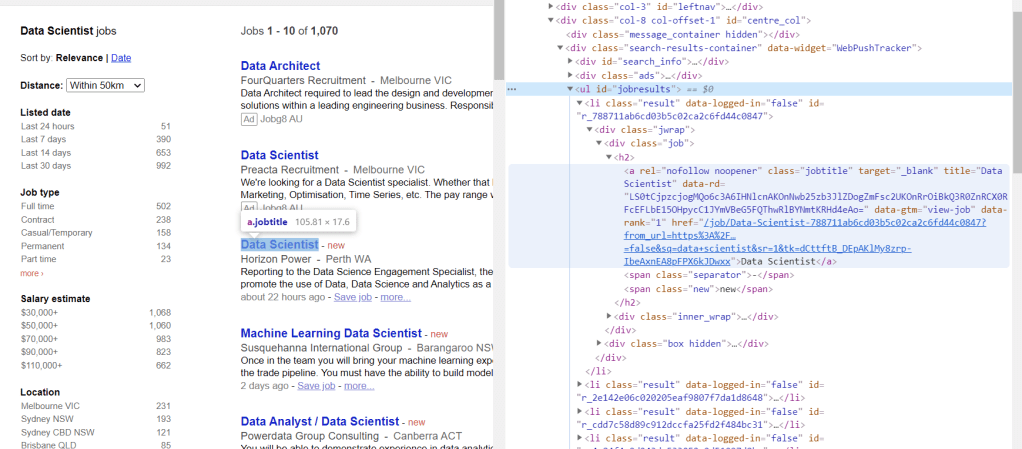

The html code of a webpage can be easily view using a browser. In Chrome, to view the html code, one can use the Developer Tool Option, which can be accessed either by the menus icon (three dots) on the top right of the browser, or by the short cut Ctrl+Shift+I. The following figure shows a typical view of the html code of a search page from Seek:

In Python, there are two key packages for web scraping: request and BeautifulSoup. The package request is used to send requests to web servers for getting the webpage content of a specified URL, while BeautifulSoup is used to parse the html code of the webpage. For example, to obtain the content of the first search page from Seek, we do the following:

import request

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

URL_base = 'https://www.seek.com.au/data-scientist-jobs'

URL = URL_base + '?page=1'

page = requests.get(URL)

soup = BeautifulSoup(page.content, 'html.parser')

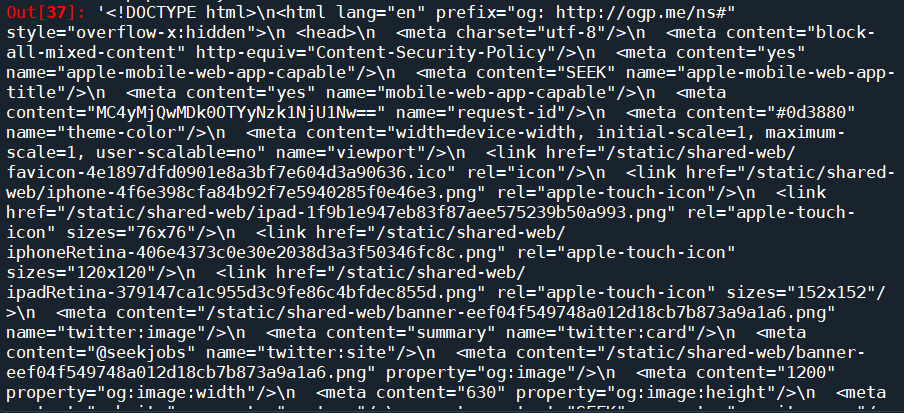

where the URL “http://www.seek.com.au/data-scientist-jobs?page=1” is the exact URL for the first page returned by typing data scientist in the search box. One can print the page content soup by using the print function, or better yet, use the build-in function prettify():

soup.prettify()

which will return the following:

We can see that this is exactly the html code we saw on the browser. We have successfully downloaded the html code of the requested page onto our script. The next step, is to parse the html to find the information that we want. BeautifulSoup provides the function soup.find() which searches through the html soup it just parsed from the webpage for tags and attributes that is passed into the function. There are general tags keywords such as class or id that BeautifulSoup recognises and can be passed relatively easily using the syntax soup.find(tag=tag attribute). It can also take in user-defined tags using the syntax soup.find(tag, attrs = {attribute:value}). So the find() function is pretty flexible and all we need to do is to find out the tags and attributes that corresponds to the part of the page that is of interest to us.

This is actually easier said then done. Firstly, you need to find a tag that has an attribute that is unique to the part of the page of interest, in order for it to be extracted. If an attribute is not unique, other parts of the page would also be extracted and it would be hard to isolate what you really need. Furthermore, if you dig around a complex search page, you will find that a lot of the attributes are random numbers and letters, probably related to how these pages are generated. These attributes are unique, but there is no way to specify it in the code to ensure that it will work every time. Most of the effort therefore comes down to slowly going through the html code on the browser, identifying the exact bits of code that corresponds to the text or the links required, and looking around the code to find a unique tag and/or attribute that can get you to this part of the code in one go.

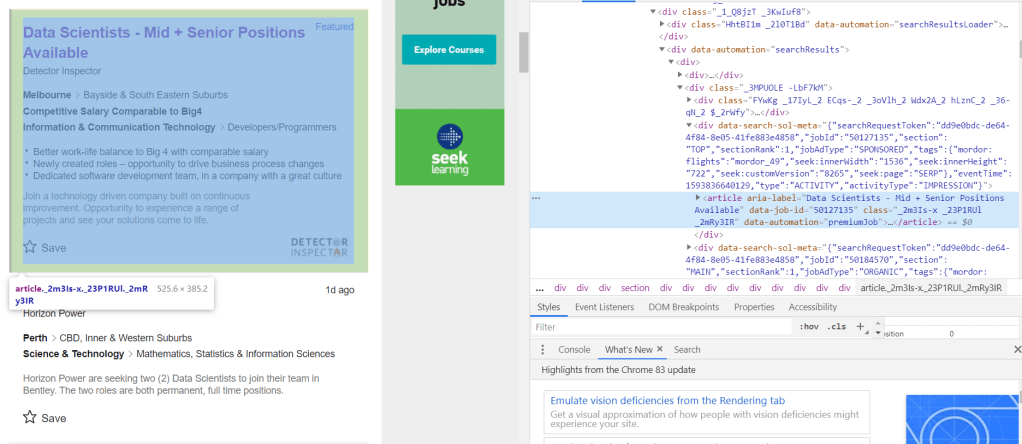

What are we really looking for? We are looking for two things – a way to access the job pages returned by the search, and the actual content of those pages. Let’s take Seek website for example. If we clicked on one of the job postings returned by a “data scientist” search, it can be seen that the webpage of the search has the following URL:

The URL starts with “https://www.seek.com.au/job”, followed by a number “50127135”, followed by a long string starting with a “?”. The part starting with the “?” actually relates to how we arrived to the page, i.e. from the search itself. The actual page can be accessed by simply using the first part of the URL, i.e., “https://www.seek.com.au/job/50127135”. If we then look at a few more jobs, it will be clear that all page URL follows the same format: a base URL “https://www.seek.com.au/job”, followed by an id that is unique to each job posting. It is likely that these job-ids can be found somewhere in the html of the search page. Following the code and keeping an eye on what bit of code corresponds to the search results (putting mouse cursor on a line of code in the chrome developer tool would show which part of the webpage is generated by that code), we find the following code snippet:

It can be seen that the job-id 50127135 is present in an attribute called “data-job-id” under the article tag. It is clear that each each result is defined by its own article tag, all of which comes under the universal tag <div data-automation = “searchResults> that encloses all search results. Since all these different tags are custom, we need to use the universal tag to extract all instances of articles within the search result, from which the data-job-id can then extracted and stored as job post URLs. This is done (for the first 8 pages of the search) using the following code:

job_link = []

job_title = []

site = []

seek_link = 'https://www.seek.com.au/job/'

URL_base = 'https://www.seek.com.au/data-scientist-jobs'

for i in range(8):

URL = URL_base + '?page=' + str(i+1)

page = requests.get(URL)

soup = BeautifulSoup(page.content, 'html.parser')

results = soup.find("div", attrs = {'data-automation':'searchResults'})

job_list = results.find_all('article')

for job in job_list:

job_link.append(seek_link + str(job.attrs['data-job-id']))

job_title.append(job.attrs['aria-label'])

site.append('Seek')

So the list of articles are extracted by first isolating the search results using the higher level tag <div ‘data-automation’ = “searchResults”>, followed by finding all article instances under this tag using the find_all() function. The attributes of the article instances can then be simply extracted using the attrs keyword.

Doing similar detective work on Indeed, the following can be found:

which yields the following code for extracting the URLs:

URL_base = 'https://au.indeed.com/jobs?q=data+scientist'

indeed_link = 'https://au.indeed.com/viewjob?jk='

for i in range(0,80,10):

URL = URL_base + '&start='+str(i)

page = requests.get(URL)

soup = BeautifulSoup(page.content, 'html.parser')

results = soup.find("td", attrs = {'id':"resultsCol"})

job_list = results.find_all("div", attrs = {'class':"jobsearch-SerpJobCard unifiedRow row result"})

title_list = results.find_all("h2", attrs = {'class':"title"})

for job in job_list:

job_link.append(indeed_link + str(job.attrs['data-jk']))

site.append('Indeed')

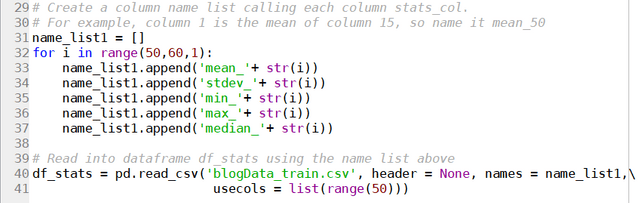

for title in title_list:

job_title.append(re.sub('\n','',title.get_text()))

Similarly for Jora:

URL_base = 'https://au.jora.com/j?l=&p='

jora_link = 'https://au.jora.com'

for i in range(5):

URL = URL_base + str(i+1) + '&q=data+scientist'

page = requests.get(URL)

soup = BeautifulSoup(page.content, 'html.parser')

results = soup.find("ul", attrs = {'id':'jobresults'})

job_list = results.find_all('a', attrs={'class':'jobtitle'})

for job in job_list:

job_link.append(jora_link + job.attrs['href'])

site.append('Jora')

job_title.append(job.get_text())

The only difference here is that for Jora, the sub-link is provided directly rather than deduced from a job id.

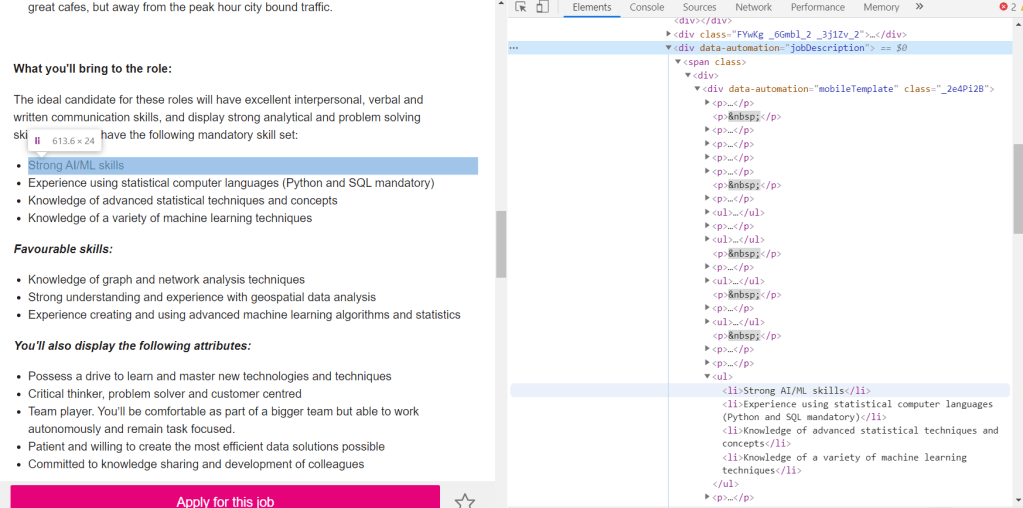

The next step is to do exactly the same thing, but looking at individual job posts, to see which part of the code corresponds to the actual text in the job ad, and extract it. Taking again the Seek job post page as an example:

It can be seen that within the text, there are two different types of tags: <p> which corresponds to paragraphs, and <li> which corresponds to lists. Both are part of the text and therefore both needs to be extracted. This is universal for all three websites. The only difference is therefore the actual tag under which these paragraphs and lists are stored. Using this information, a function can be written to extract the text of job posts according to the URL provided and the site that it belongs:

def decode_webpage(company, URL):

page = requests.get(URL)

soup = BeautifulSoup(page.content, 'html.parser')

if company == "Seek":

results = soup.find("div", attrs={'data-automation':'jobDescription'})

elif company == "Indeed":

results = soup.find(id='jobDescriptionText')

elif company == "Jora":

results = soup.find("div", attrs = {'class':'summary'})

try:

job_lists = results.find_all('li')

job_para = results.find_all('p')

corpus = []

for l in job_lists:

corpus.append(l.get_text())

for p in job_para:

corpus.append(p.get_text())

return ' '.join(corpus)

except:

return " "

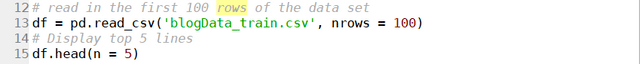

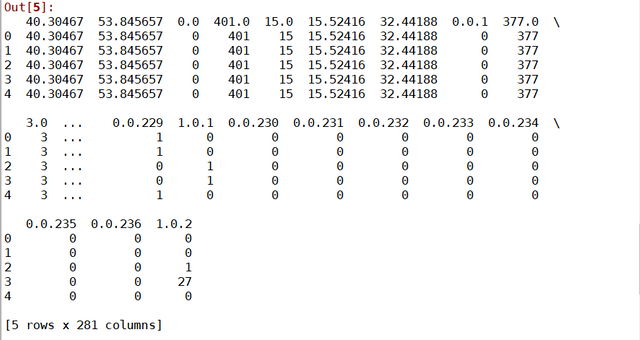

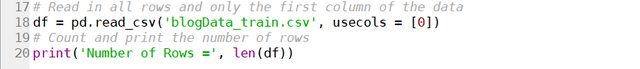

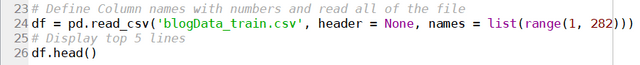

The following code then extract and stores the text from each of the extracted links into a dataframe:

import pandas as pd

df = pd.DataFrame(columns = ['job', 'link', 'site', 'content'])

df.job = job_title

df.link = job_link

df.site = site

df.content = df.apply(lambda x: decode_webpage(x.site, x.link), axis = 1)

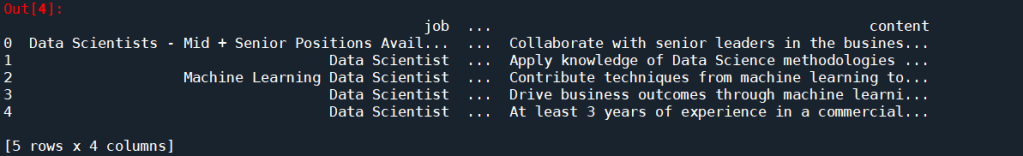

df.head()

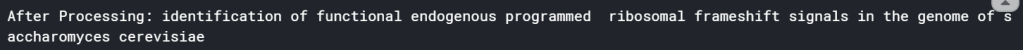

Looks like it worked pretty well. It is time to analyse the text. A simple way to extract keywords is to use the CountVectorizer() to find out what words appear the most. A simple cleaning is also performed on the text prior to the CountVectorizer().

from gensim.parsing.preprocessing import remove_stopwords

import re

def text_cleaner(text):

text = str(text).lower()

text = re.sub('[%s]' % re.escape(string.punctuation), " ", text)

text = re.sub('–', "", text)

text = remove_stopwords(text)

return text

from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import CountVectorizer

df['cleaned_content'] = df.content.apply(lambda x: text_cleaner(x))

cv = CountVectorizer(stop_words = "english")

text_cv = cv.fit_transform(df.cleaned_content)

dtm = pd.DataFrame(text_cv.toarray(), columns = cv.get_feature_names())

top_words = dtm.sum(axis = 0).sort_values(ascending = False)

print(top_words[0:20])

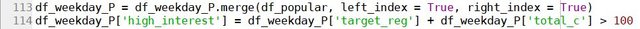

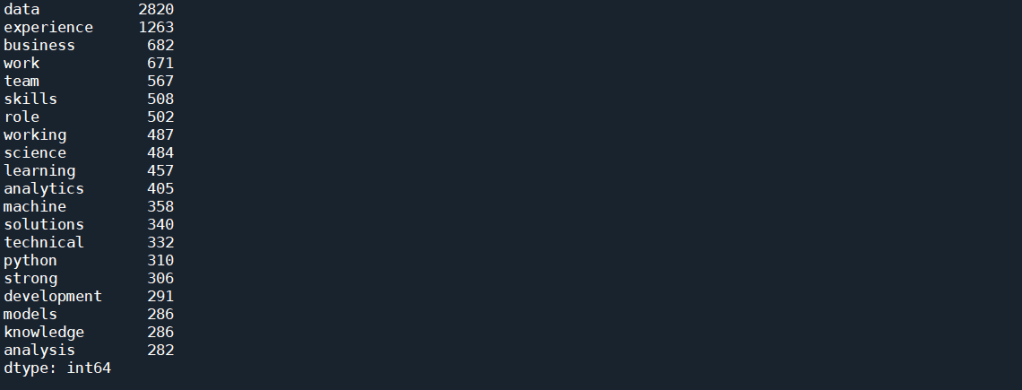

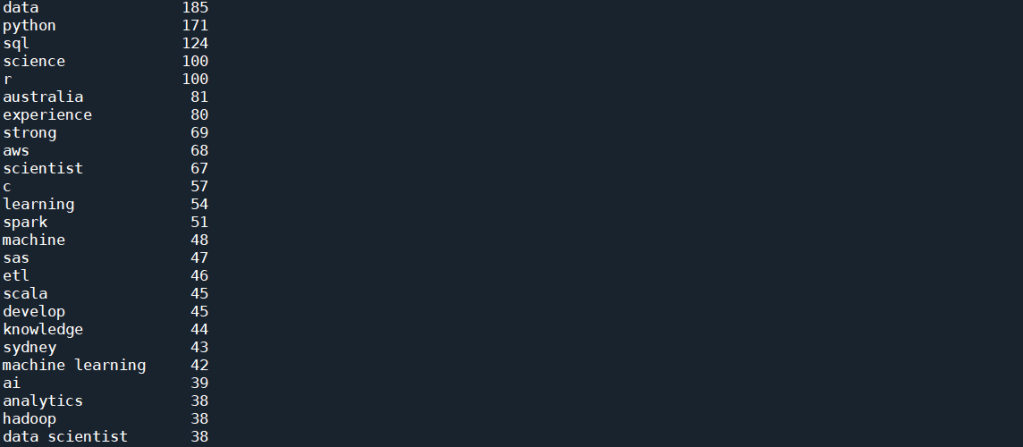

which gives the following results as the top 20 most frequent occurring terms:

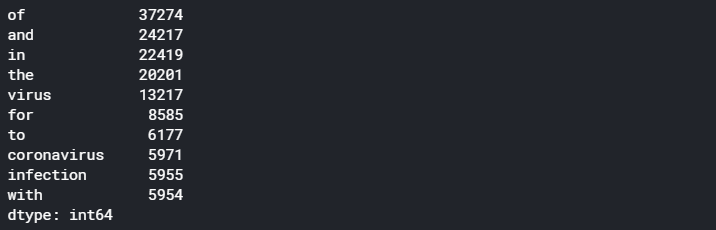

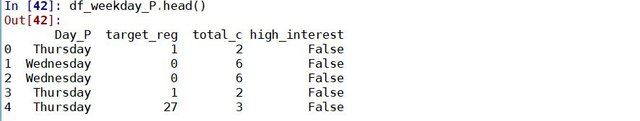

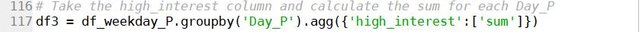

As expected, simply using CountVectorizer() does not yield good results. That’s because we know that each job posts would contain description about the job, description about the company, and other information about the job that is not relevant to this task. These general job related terms will undoubtedly occur more often then the technical skills. We would also expect words such as data and scientists occurs much more often than any other words for a search for “Data Scientist”. All these floods the term-document matrix and stops us from extracting useful information.

A way to combat this is to use Part of Speech (POS) Tag. Each word in a sentence has a role to play in that sentence – a noun, an adjective, an adverb etc. This is known as the Part of Speech. One thing that we notice with all the hard skills for Data Scientist, such as Python, AWS or NLP, are all Proper Nouns, as they are special names for a technique, method, or a software. It may therefore be a good way to isolate the skills present in the text. The nltk package provides a way to tokenise a text, with each token tagged to indicate what POS is each word in a particular sentence. We can therefore write a function to extract all words that are proper nouns in a given piece of text:

def pos_tokenise(text, pos = ['NNP']):

tokens = word_tokenize(text)

pos_tokens = pos_tag(tokens)

interested = [x[0] for x in pos_tokens if x[1] in pos]

return list(dict.fromkeys(interested))

where ‘NNP’ is the tag for proper nouns. This tag can be changed to extract out other words such as nouns or adjectives. The occurrence of any words that are repeated many times within a post is also reduced to 1 (using list(dict.fromkeys())). This is because we are only interested in what words appears in most job posts, and not how many times a word appears within one job post. We can then apply this function to the text that extracted from the job ads as follows:

df['nouns'] = df.content.apply(lambda x: pos_tokenise(str(x)))

df['cleaned_nouns'] = df.nouns.apply(lambda x: text_cleaner(" ".join(x)))

df.drop_duplicates(subset = 'cleaned_nouns', keep = 'first', inplace = True)

Note that the cleaning is performed after the nouns were extracted, to avoid turning proper nouns to lower cases which would mean they can’t be detected. Note that here, we are also removing duplicates, as it is very likely that some jobs are posted on multiple sites. Next, we apply the CountVectorizer() again on these proper nouns:

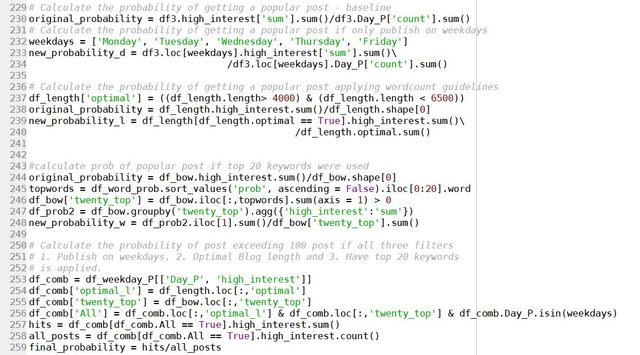

cv = CountVectorizer(token_pattern = r"(?u)\b\w+\b", ngram_range = (1,2))

text_cv = cv.fit_transform(df.cleaned_nouns)

dtm = pd.DataFrame(text_cv.toarray(), columns = cv.get_feature_names())

top_words = dtm.sum(axis = 0).sort_values(ascending = False)

print(top_words[0:25])

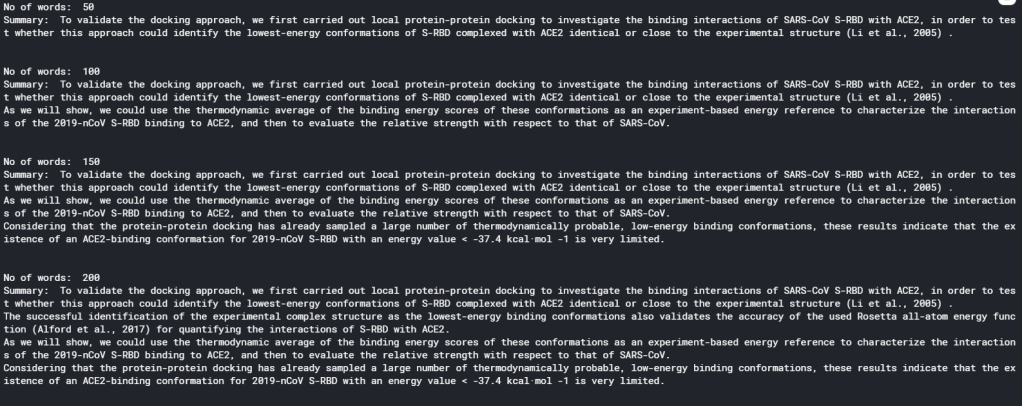

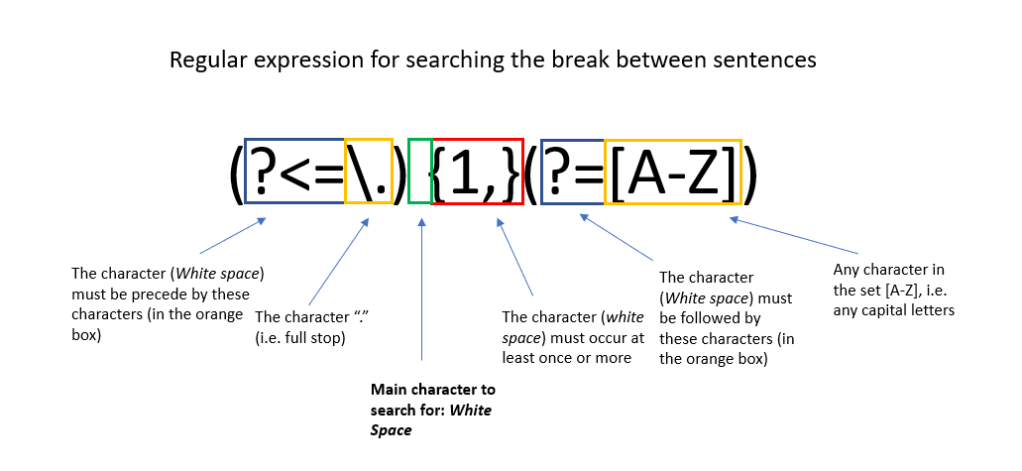

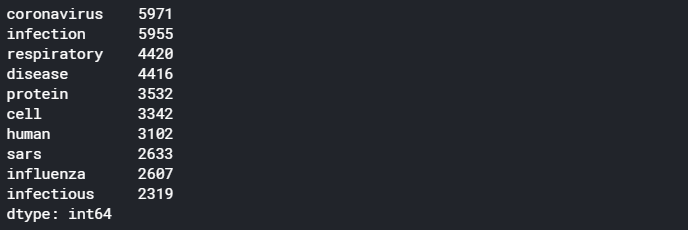

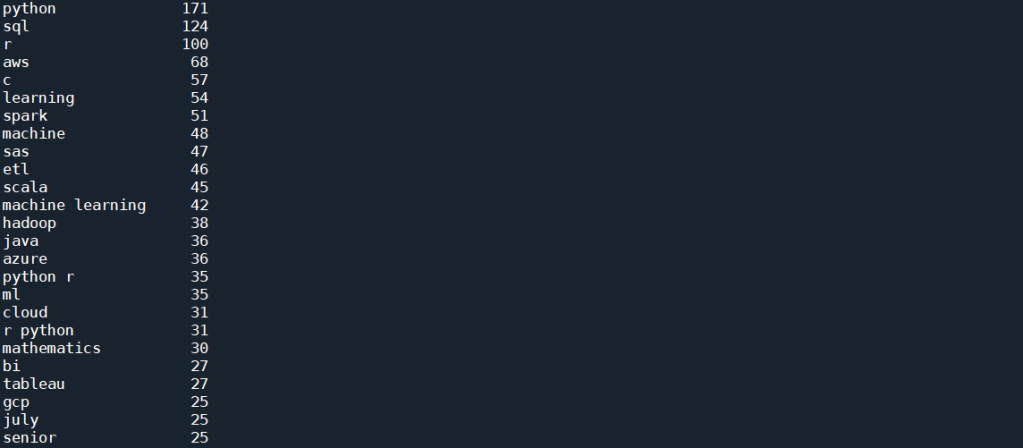

Two things to note here. Firstly, a token pattern “r”(?u)\b\w+\b”” is passed into the CountVectorizer() to take care of tokens that are only 1 letter long, as by default, CountVectorizer() disregard tokens that are less than 2 letter long. This is important as one of the important skills, R, is obviously a single letter token. Another thing to note is that a ngram_range = (1,2) means that n-grams of up to 2 words (i.e. bi-grams) will be considered as a candidate for the vocabulary. The code above produces the following results:

This is much better. We start to see a lot of skills showing up in this top list, which includes Python, SQL, R, AWS, C and Spark. There is still a lot of other words, such as “data” and “science”, and some of them are not even nouns, for example, “develop” or “strong”. This artefact in the result is due to the fact that in most job ads, the required skills are emphasis in lists, which most often then not have every single word’s first letter capitalised. The fact that NLTK simply rely on the capital letter to identify a proper noun result in these words being selected along with what we actually want.

We can look into more sophisticated approach to remove the unwanted words. But from the list above, it can be seen that we are almost there – more than half of those words are actual skills. If the objective is to find the most common skills advertised, the quickest way forward is in fact manually remove the words that we don’t want, since the word list is already down to a manually manageable size. We can therefore look through the list, and manually put the words that we don’t want as stop words, and run the CountVectorizer() again:

stop_word_list = ['data', 'science', 'experience', 'australia', 'scientist', 'strong', 'develop', 'sydney', 'ai', 'analytics', 'engineer', 'phd', 'apply', 'work', 'design', 'knowledge', 'role', 'big', 'proven', 'engineering', 'skills', 'cv', 'research', 'build', 'excellent', 'business', 'ability', 'platform']

cv = CountVectorizer(stop_words = stop_word_list, token_pattern = r"(?u)\b\w+\b", ngram_range = (1,2))

text_cv = cv.fit_transform(df.cleaned_nouns)

dtm = pd.DataFrame(text_cv.toarray(), columns = cv.get_feature_names())

top_words = dtm.sum(axis = 0).sort_values(ascending = False)

print(top_words[0:25])

which gives the following:

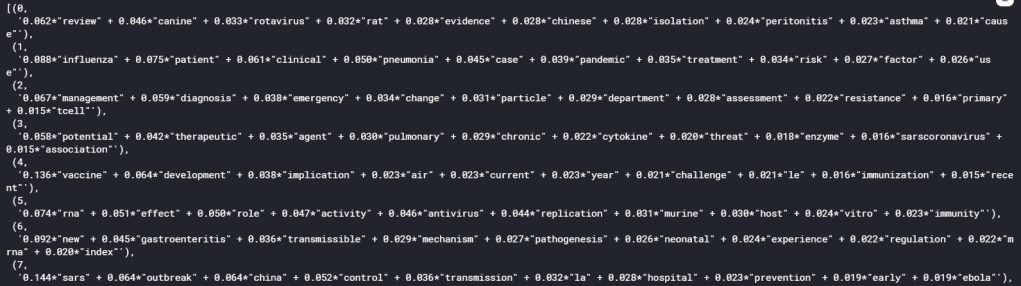

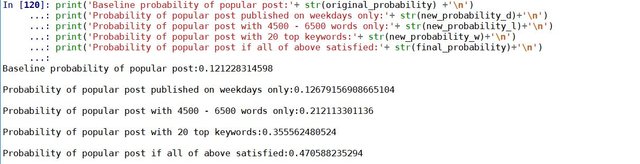

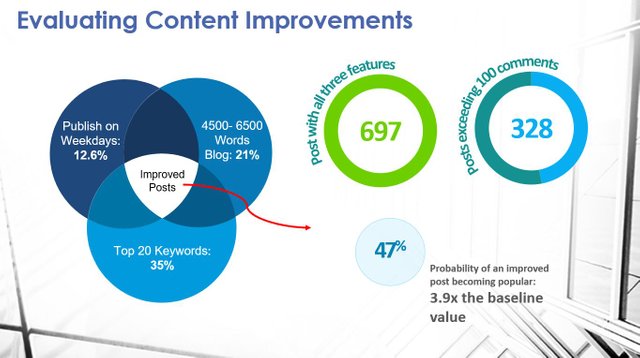

This is already giving us very interesting results. As can be seen from the list, as expected, the top skill that has been most mentioned, listed in 171 posts, is Python. This is followed by SQL and R, both of which are also expected. It is, however, interesting to see that next up is AWS and C (with C representing both C and C++ and C# etc as all punctuation has been removed), followed by Spark, SAS, and perhaps quite unexpectedly, ETL (Extract, Transform, Load) – i.e. database operations. Machine Learning is interesting, in that there are 54 and 48 mentions of Learning and Machine respectively, but only 42 of those actually comes from the bi-gram “machine learning”. However, there is also “ml” which in these job posts are most definitely short hand for machine learning, and therefore should actually be counted towards the total mention.

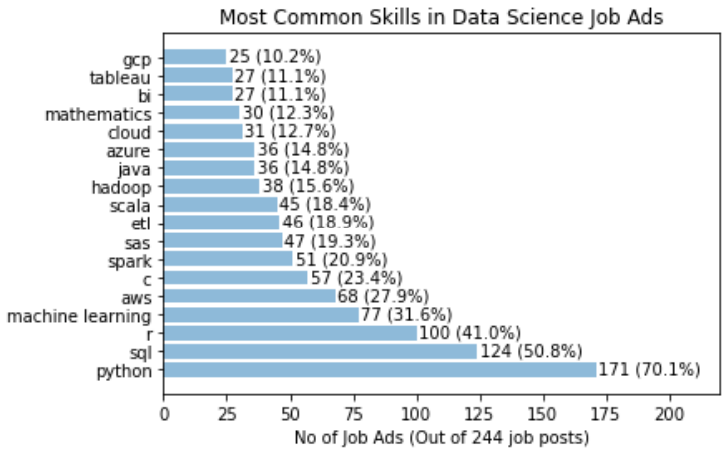

To visualise these results, we take this list of 25 top terms and further clean it:

important_skills = top_words[0:25]

important_skills.pop('july')

important_skills.pop('senior')

important_skills.pop('learning')

important_skills.pop('machine')

important_skills['machine learning'] = important_skills['machine learning'] + important_skills['ml']

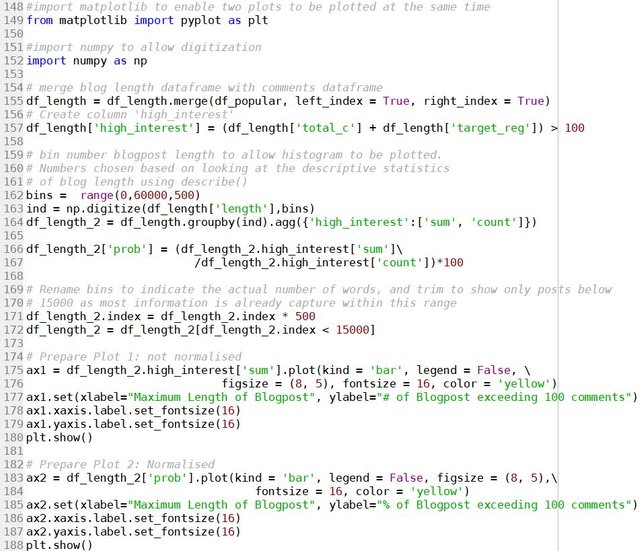

important_skills.pop('ml')

important_skills.pop('python r')

important_skills.pop('r python')

sorted_skills = sorted(important_skills.items(), key=lambda x: x[1], reverse=True)

skills = [x[0] for x in sorted_skills]

occurrence = [x[1] for x in sorted_skills]

Here, we have combined the counts of machine learning and “ml” to get a true count of “machine learning” in the posts. “python r” and “r python” are also removed, as the count of these will already be included in “python” and “r” individually.

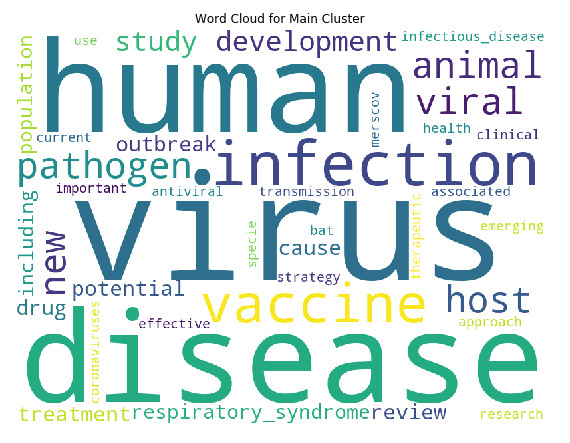

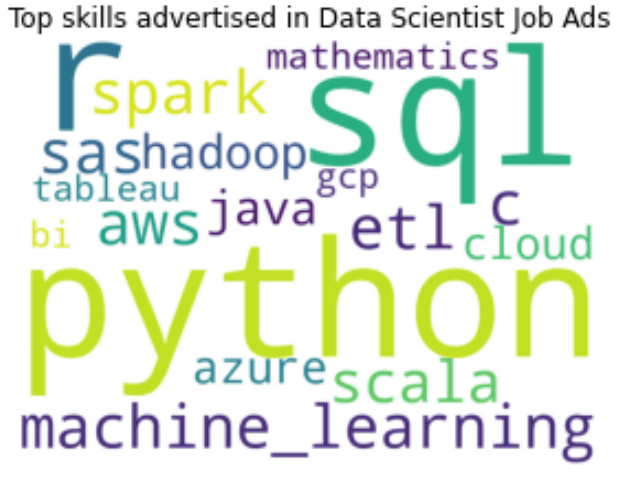

We can now visualise these skills. First, let’s form a word cloud:

from wordcloud import WordCloud

topword_string = ",".join(skills)

topword_string = re.sub("machine learning", "machine_learning", topword_string)

wordcloud1 = WordCloud(width = 800, height = 600,

background_color ='white',

min_font_size = 10, regexp = r"(?u)\b\w+\b", normalize_plurals = False,

relative_scaling = 0, stopwords = set()).generate(topword_string)

plt.figure(figsize=(5,3))

plt.imshow(wordcloud1)

plt.title("Top skills advertised in Data Scientist Job Ads")

plt.axis("off")

plt.tight_layout(pad = 0)

plt.show()

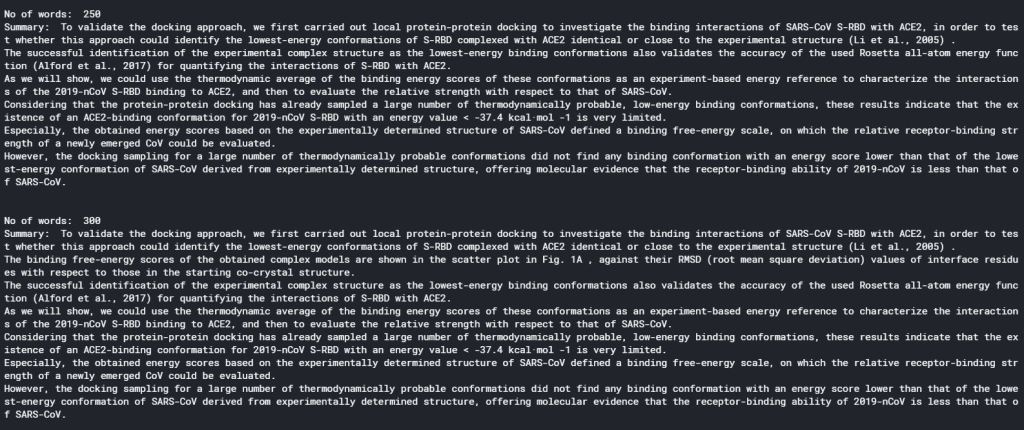

Note the need to remove all stopwords and specify regexp to include “C” and “R” in the wordcloud. The relative_scaling = 0 means that font size is determined by rank only. The following wordcloud is generated:

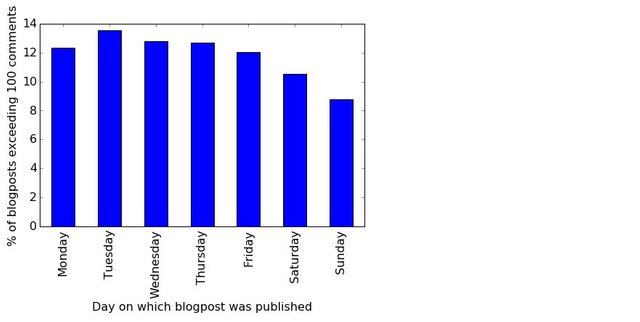

It can be clearly seen here that Python, SQL and R are the top three skills mentioned in data scientist job advertisements. This is followed by Machine Learning and AWS. SAS, Spark, Scala and ETL also have similar font sizes, and therefore are also mentioned quite often. For a more quantitative visualisation, we can look at the total number and proportion of job ads that each skill is mentioned in:

y_pos = np.arange(len(skills))

plt.barh(y_pos, occurence, align = 'center', alpha = 0.5)

plt.yticks(y_pos, skills)

plt.xlabel('No of Job Ads (Out of ' + str(len(df)) + ' job posts)')

plt.xlim(0,220)

plt.title('Most Common Skills in Data Science Job Ads')

for i in range(len(occurence)):

label = str(occurence[i]) + " (" + "{:.1f}".format(occurence[i]/len(df)*100) + "%)"

plt.annotate(label, xy=(occurence[i] + 1 ,y_pos[i] - 0.22))

plt.show()

which gives the following:

It is clear that Python definitely takes the crown, with 70% of the job posts mentioned Python. SQL is also popular, with over 50% of job posts requiring SQL. This is followed by 41% for R. Interestingly, only 32% of jobs specifically mention the need of machine learning. A similar proportion of jobs have AWS mentioned. C, Spark, SAS, ETL and Scala all have a similar proportion siting at around 20%.

Another way to visualise the data is to look at for each skill in the list, what other skills is mentioned together the most often. To simplify, we will only consider the top eight skills for this analysis, but for each of these we will look at all the skills extracted above to see which one is the most frequent co-skill:

top_8 = skills[0:8]

df_2 = pd.DataFrame()

for s in top_8:

df_2[s] = df.cleaned_nouns.apply(lambda x: " ".join(skill_relations(skills, s, x.split())))

cv = CountVectorizer(token_pattern = r"(?u)\b\w+\b", ngram_range = (1,1))

text_cv = cv.fit_transform(df_2[s])

dtm = pd.DataFrame(text_cv.toarray(), columns = cv.get_feature_names())

top_words = dtm.sum(axis = 0).sort_values(ascending = False)

co_skills = top_words[0:8]

sorted_top_skills = sorted(co_skills.items(), key=lambda x: x[1], reverse=True)

top_skills = [x[0] for x in sorted_top_skills]

top_occurrence = [x[1] for x in sorted_top_skills]/important_skills[s]*100

y_pos = np.arange(len(top_skills))

plt.barh(y_pos, top_occurance, align = 'center', alpha = 0.5)

plt.yticks(y_pos, top_skills)

plt.xlabel('% of Job Posts')

plt.xlim(0,120)

plt.title('Skills that appear most often with: ' + s.upper())

for i in range(len(top_occurrence)):

label = "{:.1f}".format(top_occurrence[i])+ "%"

plt.annotate(label, xy=(top_occurrence[i] + 1 ,y_pos[i] - 0.22))

plt.show()

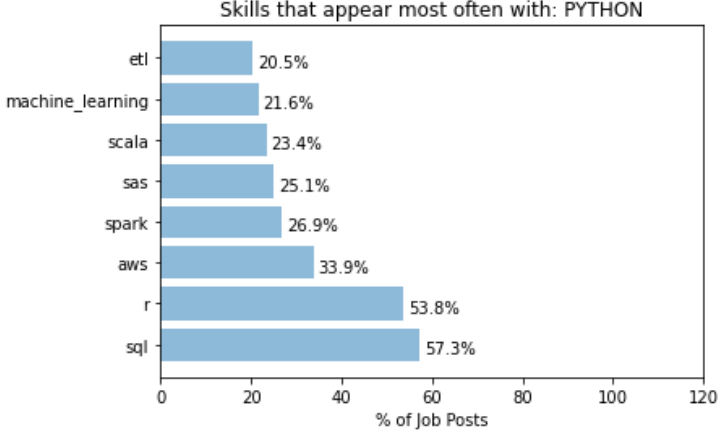

For example, when a job post mentions Python, the following graph shows which other skills is most often mentioned together:

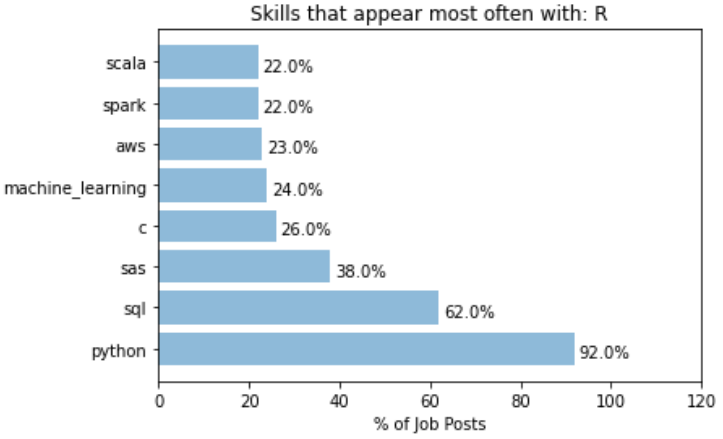

It can be seen that over 50% of job posts with Python also mentioned SQL and R, and over 30% mentions AWS. On the other hand, we have the following for R:

A whooping 92% of job posts that mentioned R also mentioned Python. This indicates most job posts that asks for R also accepts Python users, but not vice versa. In that sense, learn Python probably open up more opportunities than learning R. For R, SQL is also another common co-skill that employers mention in their job ads.

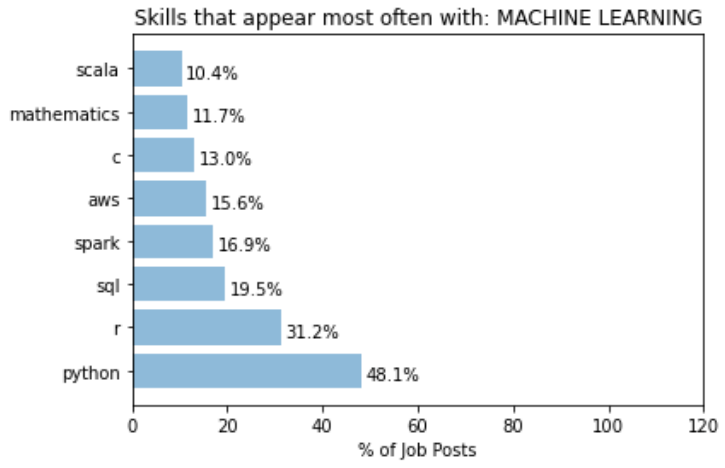

A different behaviour is observed for the keyword “machine learning”:

Posts that mentions machine learning has a lower proportion that mentions Python. This suggests that a more machine learning focus role is probably less focused on what language you use. A even lower proportion mentions SQL, significantly lower than expected from a random set of posts. This could simply mean that most role that focuses on machine learning probably require less direct data extraction and manipulation in databases. Or, it could be from the fact that what is done here does not take into account the fact that not all search results returned are data scientist roles. May be a significant portion that mentions SQL are actually Data Analyst roles, as oppose to those that mentions “machine learning” are proper data scientists roles. This is one of the key things in the current approach that needs to be improved on.

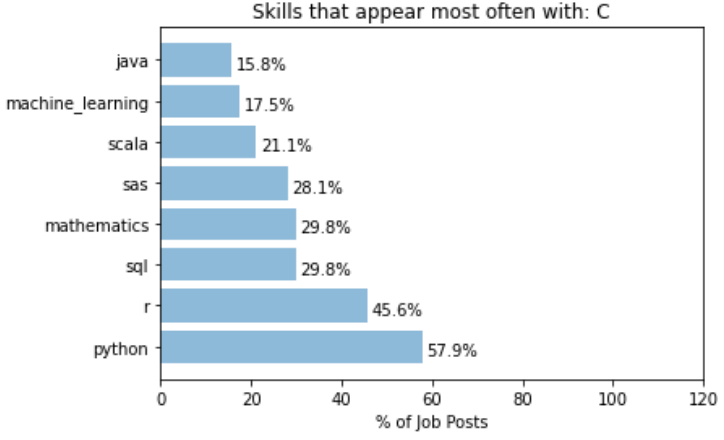

While most of the top skills seems to have top co-skills that is within the 8 top skills list, there are certainly cases where skills that appears more often with a particular key skill than it otherwise would. For example, let’s take the analysis for “C”:

It can be seen that the word “mathematics” is almost 3 times more likely to appear with “C” than it normally would. This can be interpreted as C (or C++) is a much more commonly used language for jobs that involves really digging into the mathematical models of data science, such as research or postdoctoral positions.

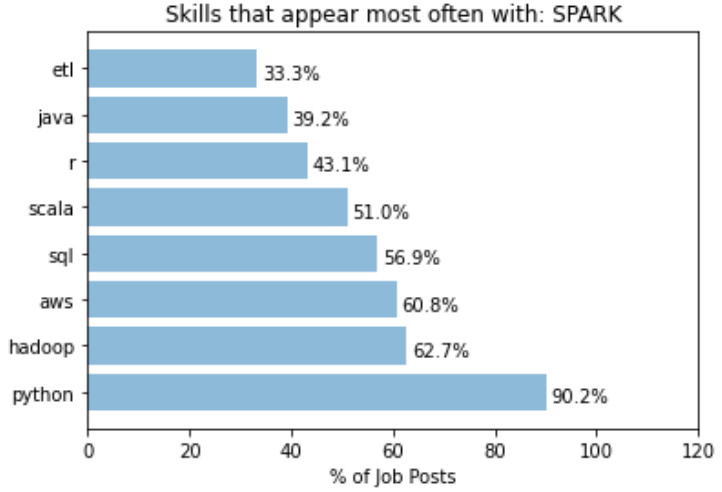

Another example of specific co-skills is with the word “Spark”:

While python still takes out the dominant spot in this case, we can see that the “Hadoop” is 4 times more likely to be mentioned in job posts with “Spark” mentioned. This is expected as Hadoop and Spark are from the same eco-system, but highlights the fact that someone having Hadoop in addition to Spark in their knowledge base would fair better in these jobs than someone who just know one but not the other.

To conclude, we have successfully extracted information from data scientist job posting using BeautifulSoup and POS analysis, and obtained a list of top data science skills that are most mentioned in the job postings. The approach here was semi-manual: Manual filtering of words that are not relevant was required to clean the keyword list to a desirable form. Obviously, more work can be done on perfecting the keyword extraction process, by making it more automated and generic. For example, comparison with a set of reference pages may potentially allow irrelevant terms to be removed. There is a whole set of literature looking at different ways to do domain specific term extraction in an unsupervised way. There is also improvements in terms of how the problem is framed and approached. For example, we may want to narrow down the difference between data scientist vs machine learning engineers vs data analysts, to give a more meaningful breakdown. POS analysis with adjectives or adverbs may also prove helpful in extracting the soft skills required, such as being inquisitive or a quick learner.

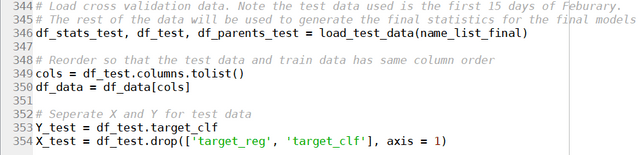

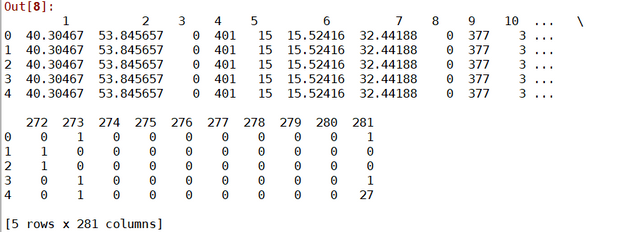

But the initial goal of this exercise, which is to find out what specific skills is needed to have a better chance at becoming one, has been achieved. As someone who do want to become a data scientist, it is clear that my immediate attention should be given to improving my skills in SQL and AWS (given that I have pretty good skills in Python, R and machine learning), rather than perfecting this project. So expect stuff about my learning in SQL and AWS in my next blog!